This is a selection of interesting historical churches in east Ross-shire and Sutherland. The descriptions are based on work by conservation architect Andrew Wright for the East Church conservation plan.

All the churches Andrew looked at are typical examples of a Post-Reformation church. They all reflect similar historical, social, economic, and religious influences and share liturgical layout, construction and architectural features. The principal construction work at each church was undertaken by the end of the eighteenth century.

The Gaelic Chapel, Cromarty

The Gaelic Chapel, Cromarty

Now a ruin, the Gaelic Chapel was built as a new church in 1783 by George Ross of Pitkerrie, who had bought the Cromarty Estate in 1767. It is on a prominent position overlooking the town, and was built to house gaelic speaking workers who had moved to work in Cromarty. In the early nineteenth century it had 500 worshippers.

The nave is a plain rectangle, with lofts at either end. The height of the belltower, replacing the more common bellcote, provides emphasis to the east end of the building.

During the First World War the building was used by troops, but afterwards was declared redundant to worship. The church came back into use in the Second World War when it was used by Polish troops as a garrison chapel and was well cared for. But by the late 1950s the roof had collapsed under its own weight, and the pine pews, the pulpit with a Roman Doric entablature, its’ sounding board and precentor’s desk were all stripped out and the walls of the ruin consolidated.

The porch and the belltower retain their slated roofs, although they are now in poor repair. The arched windows to either side of the pulpit, together with the openings of the porch and the tower, display the characteristic architectural features of keystones and impost blocks.

Kiltearn, old parish church, Alness

Kiltearn, old parish church, Alness

In a tranquil setting by the north shore of the Cromarty Firth the gaunt ruin of Kiltearn still conveys a sense of past grandeur. The classical detailing is elegant and the proportions convincing, reflecting the fact that the

reconstruction of the church was carried out mostly as a single operation in 1790-1.

In the southeast corner the relics of a medieval predecessor kirk survived this work - the fragments of an east window and corner buttresses confirming the east-west orientation of the medieval foundation.

The scale of the redevelopment of Old Kiltearn reflects the status of the Munros of Foulis, whose loft was erected, unusually, to the south of the vastly widened medieval nave. The loft has a generous double forestair leading up to a door in the gable with a fine entablature; in turn this led to two retiring

rooms behind the loft screen, each with its own fireplace.

The congregation entered through doors at either end of the south wall of the nave – a common arrangement – but because of the position of the Foulis aisle the pulpit is unusually located on the north wall of the nave. Although most of the harled surfaces have been lost it is clear that the church would have been harled and limewashed. The bellcote is plain and well-proportioned, located at the west gable, lacking the more usual corner pinnacles or a crowning finial.

The church was declared redundant after the Second World War. The roof has been removed and the interior stripped out and, while the ruin is presently accessible, there are no formal arrangements for access.

Alness old parish church

Alness old parish church

Another roofless ruin, located on the same coastal plain within a few miles eastwards of Kiltearn, but the setting of the old parish church of Alness is quite different, overlooking the firthlands to the west and east from an elevated position, surrounded by a medieval graveyard now substantially added to.

Originally the church would have been the focus of a medieval settlement, with a mill and alehouse in close proximity, and with a castle motte to the northeast of the site. Ultimately the town of Alness shifted eastwards, leaving the church, manse and the glebelands isolated from the community it served had served for so long.

The inspired patronage of the Munros of Novar, Teaninich and Lealty resulted in a rich legacy of funerary monuments. The Novar loft had been a particularly fine affair, with coloured plasterwork of the highest quality. The nave walls are founded on those of the medieval church and, once more, the orientation is east-west. An unusual feature of the building is what is considered to have been a carriage-house below the retiring rooms to the rear of the loft, which results in an additional extension to the customary T-plan,

with the transeptal aisle in the normal position to the north.

The transformation of the medieval kirk to a recognisably Post-Reformation was gradual, confirmed by the distinctive datestones of 1625, 1735 and 1775, carved at intervals to the skews of the west gable, which at one stage represented the principal entrance to the site.

The bellcote presides over the same gable and, until recently, it was pinnacled at the four corners with a central obelisk. Although repairs and alterations were undertaken to the fabric in the nineteenth century they were minor and, essentially the character of the late eighteenth century interior had been preserved.

The building had been limewashed white.

Regular worship ceased in 1936, and during the Second World War the interior was used as an army store. In the mid-1960s the interior was stripped of its furnishings, and by 1970 the roof was removed and the wallheads protected with haunching. At present the ruin is somewhat emaciated, having been stripped of its principal carved panels and finials at the heads of the gables; although set aside for possible reinstatement these distinctive features appear to have been lost. The ruin is presently boarded up, and inaccessible.

Nigg old church

Nigg old church

The long, low profile of the principal elevation of the church has undoubted charm, revealing its origins in the early seventeenth century, although the foundation of the church is most likely to be medieval, most probably on an early Christian site.

The pictish Nigg stone, on display within the former south porch of the church, and medieval gravestones within the historic graveyard would seem to give support to this view. As elsewhere, yews grow within the graveyard. Unusually, the orientation is closer to north-south than east-west, with the bellcote on the south gable, a fine example, with finials adorning each of the corner pinnacles and the central one, and with finely incised mouldings cut in the face of the pillars.

Alterations were made in the early eighteenth century. The transeptal aisle, to the north, was added in the 1780s, giving the building a different character to the rear. The roof pitch to the simple rectilinear nave may have been reduced at the same time, and the elongated windows inserted to either side of the pulpit.

The lofts remain in position at each end of the nave in their original form behind partitions erected when the interior was recast in the nineteenth century resulting in a plain, somewhat incongruous interior.

When the church was declared redundant the Nigg Old Trust was formed to care for the church and the outstanding Pictish carved stone, re-sited under cover within the former south porch.

You can find out more about Nigg Old church on their website.

Tarbat old church

Tarbat old church

Old Tarbat Church is yet another historic church declared redundant for worship, its future secured by a trust; here the building has been given new life as a museum - the Tarbat Discovery Centre - recognising the significance of the archaeological excavations to the southeast of the site where the possibility of a Pictish monastic settlement has emerged. The east-west orientation of the church, and the substantial underbuilding below the nave suggest at the very least an early medieval site and documentation confirms that there had been a church here in the mid-thirteenth century. The church occupies a prominent site overlooking the village and harbour of Portmahomack.

The approach to the church is dominated by the massive belltower, thought to date from the early seventeenth century, which also houses a doocot, marking the church out from the others under study here.

The approach to the church is dominated by the massive belltower, thought to date from the early seventeenth century, which also houses a doocot, marking the church out from the others under study here. The former door openings leading to the original lofts each have forestairs, as does the loft to the north transeptal aisle. The south elevation has been modified by the insertion of three vertical windows instead of the more usual two. The vertical emphasis to the glazing and the larger panes suggest that they were inserted at the time when the church was reordered along ecclesiological lines in the late nineteenth century. The pulpit and sanctuary screen remain in position forward of the east gable where the dais is raised.

Old Edderton parish church

Old Edderton parish church

The church sits below the level of the public road, relating to the estuarial floodplain of the Dornoch Firth to the north. The orientation, once more, is east-west. The present structure may be dated reliably to 1743, although the burial aisle to the east of the present structure, of 1631, gives a strong impression of having been roofed, and part of an earlier church.

The high ground levels around the church suggest that this is a medieval church site. Archaaeological excavations in the nave of the church, undertaken at the time of carrying out the comprehensive scheme of repairs to the fabric, confirm the supposition that the floor had been raised. Although the church interior has been recast with late nineteenth century pews much of the character of the Post-Reformation church remains.

The church has a charming domestic scale, preserved carefully in the alterations of the nineteenth century when leaded lights in clear glass were introduced. The dormers are treated similarly, and are unobtrusive. Quoins and margins to window and door openings are of plain sandstone with

square arrises, contrasting with the harled wall planes, limewashed white.

The preservation of this redundant church has been secured, as at Nigg, by a dedicated local charitable trust.

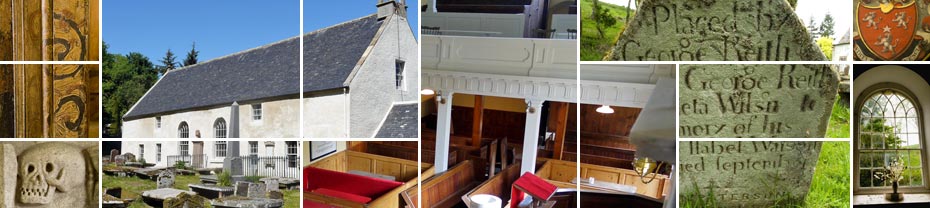

Golspie Parish Church

Golspie Parish Church

St Andrew’s Parish Church, Golspie, is the only site to fall outside the principal study area of Ross and Cromarty and, extraordinarily, it is the only church that remains a place of worship today. Of the eight churches under study it is the only one included by John Hume in his personal selection of Scotland’s best churches, considering it to be ‘one of the least altered eighteenth century churches in Scotland’

John Gifford in the Highland volume of the Buildings of Scotland series agrees, using similar words to those used to describe Cromarty East Church, as the ‘epitome of the Georgian parish kirk’. Hay in his seminal work rated it, with Cromarty, among the eight most significant of all Post-Reformation churches.

The plan, having primarily an east-west orientation, is most likely to have its origins in the seventeenth century when the parish church was relocated to the present site, and the present layout and appearance would have followed the addition of the north transeptal aisle in 1738. The plan then became cruciform after the addition of the south aisle in 1754. The roof pitch is significantly steeper than many of the comparable churches of Easter Ross, identifying the principal construction period as being the second quarter of the eighteenth century. Elsewhere, where rebuilding took place at a later date, the wallheads would be raised, and the more fashionable lower roof pitch of the late eighteenth century would be adopted. This was often the case when new aisles were added.

The splendour of the interior no doubt reflects the longstanding association with the Sutherland family, whose aisle is to the north of the plan, approached by a forestair. In common with the churches with which the Ross-shire Munros were involved, it had a retiring room, and may have been the inspiration for them to emulate similar levels of comfort.

The splendour of the interior no doubt reflects the longstanding association with the Sutherland family, whose aisle is to the north of the plan, approached by a forestair. In common with the churches with which the Ross-shire Munros were involved, it had a retiring room, and may have been the inspiration for them to emulate similar levels of comfort. The ornate coloured treatment of the loft front and surround of 1739, and the painted ceiling, are in stark contrast to the plain boxed pews of the interior which have a dignified, and remarkably uniform appearance which was maintained even when new pews were added in the mid-twentieth century.

You can find out more about St Andrews, Golspie on their website.

Become a friend

Support the work of the Scottish Redundant Churches Trust in looking after historic buildings like the East Church. more »“The support of the people of Cromarty during our Restoration Village bid was fantastic and we are looking forward to working with the community again as the Church undergoes major conservation and repair work.”

Victoria Collison-Owen, SRCT Director